Start a conversation about dog training methods and you’re likely to wish you’d brought up politics instead.

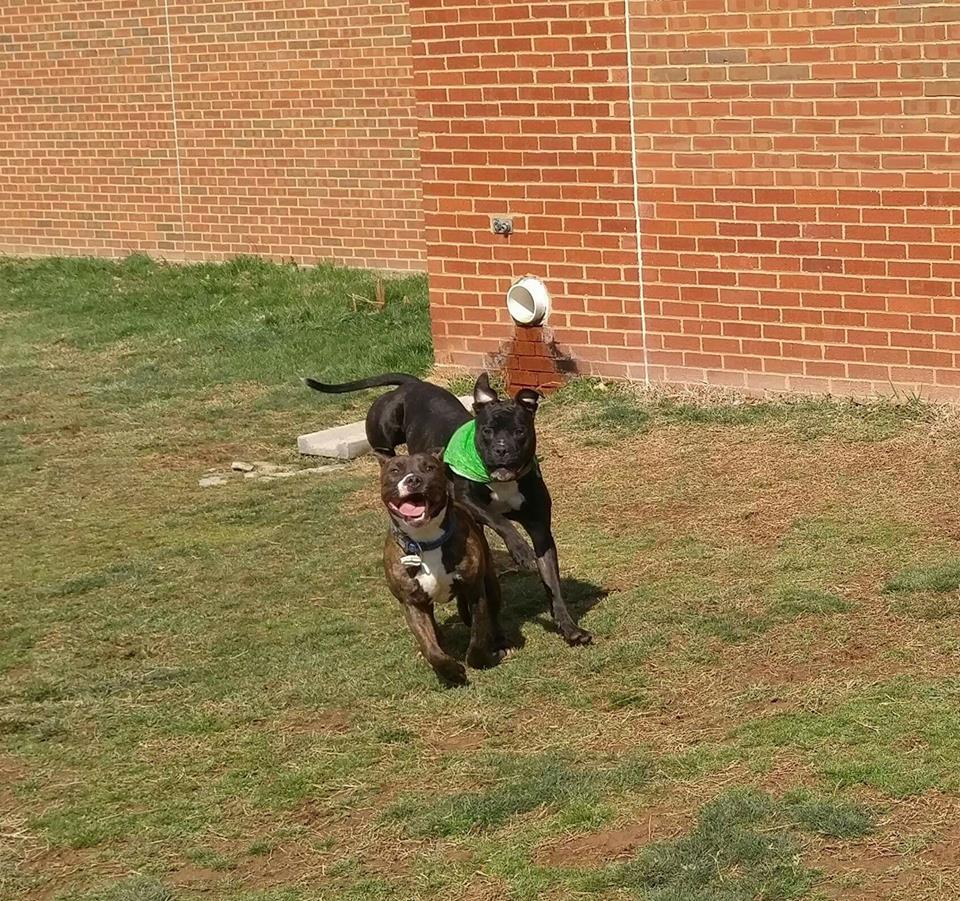

When I started working with homeless dogs, I quickly gravitated to the “long-stay shelter dogs.” These tend to be big, young adult dogs who never had any guidance as puppies as well as dogs who just need a whole lot of mental and physical stimulation — you know, the ones who really need a job! Nearly all of them also develop strong, loving bonds with their human friends; it was impossible not to fall in love with these affectionate, smart, energetic pups.

At that time, I was open to any training technique under the sun. I hadn’t applied my animal behavior and psychology education to the dogs in front of me. Not yet.

The dogs I was working with were living in a kennel-based shelter, which, no matter how compassionately run, is going to be very stressful for many animals. So any training or behavior modification we tried was two steps forward, one step back.

As I desperately searched for ways to save my canine buddies, I picked the brains of trainers from many disciplines with varying levels of skill, experience, and education. One trainer I talked to back then told me in an earnest whisper, “more cookies won’t save Fido.” I nodded my head in agreement, thinking “yeah, we might need some ‘tough love’ to save this dog” (a previously abused husky who had bitten). And then he told me that he starts by food-depriving the dog for a couple of days. I walked away.

Another trainer, who has been so very committed to helping homeless pit bulls and German shepherds, wanted me to “pop” a dog — a lovely pit bull mix I knew well — who was wearing a prong collar. This was sincerely meant to help the dog with his leash manners to improve his chances of being adopted. I refused because I knew by this time that this kind of punishment is not necessary and can have serious negative consequences. My concern for the dog’s welfare was well rewarded — I was kicked out of the training class.

Do these trainers have evil intentions? Absolutely not. They want to save all the puppies too! They want to help restore the human-dog bond. But their methods bear too much risk. Why? Two words: classical conditioning.

Usually, in dog training, we focus on the carrots and the sticks; rewards and punishments. That’s “operant conditioning.” But while we are focused on rewarding the behavior we like and punishing the behavior we don’t like, another form of learning — classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning — is happening all the time … whether we want it to or not! It’s like an app that’s running in the background — but you can’t uninstall!

To be brief, classical conditioning can change the emotional value of something the dog encounters in the environment. For example, Pavlov himself paired an initially neutral stimulus (the ring of a bell) with something the dogs already considered pleasant (food). By repeatedly following the ring of a bell with food, Pavlov’s dogs developed a positive association with the bell, as indicated by their happy drooling when they later heard the bell and did not immediately receive food.

You can use classical conditioning in a similar way to help dogs feel better about something they currently find upsetting (like the sight of other dogs, men in hats, etc.). But if you use aversive stimuli in your training, you might inadvertently cause classical conditioning to occur in a potentially unhelpful, or even dangerous way.

For example, if your dog barks, lunges, and generally acts like a maniac when she sees other dogs, and every time you respond by giving her a leash correction (a very common approach), then you are repeatedly pairing the sight of another dog with something unpleasant. Depending on the type of collar, physical characteristics of the dog, and how aroused the dog is in that moment (among other things), that unpleasant stimulus might be perceived as anywhere from mild discomfort to severe pain. Although the dog may reduce her tendency to react like a nut (yay!), the emotional value of other dogs has worsened (drat!), and this likely means that the improvement in behavior will be short-lived and unreliable. Round a corner and come face to face with another dog unexpectedly, and you’ll see evidence that she still actually finds other dogs upsetting — and probably more upsetting than prior to your training — because she’ll explode in a barking snarling, out-of-control fury. Cue the embarrassment!

What’s worse is, the timing of the punishment, among other factors, can affect which stimulus the dog pairs with the punishment. And this is not a conscious process; there’s no reason to expect awareness by the dog of what’s happening to her feelings. Dogs have been known to associate the punishment with other dogs, certain locations, and (scariest of all) humans: unfamiliar people, certain categories of people (like toddlers), or even their owner. Having a dog who acts like a maniac when she sees other dogs is difficult; having a dog who has become aggressive toward humans is way worse!

What about e-collars? I know they’re popular, and, like many people, I was curious at first. I’ve had many e-collar trainers demonstrate the low level of shock (just a tingle!) they aim for. I’ve listened, asked questions, and watched how they work. My initial reaction several years ago? “Neat!” I learned that, in contrast to the past use of the device (for “positive punishment,” see below), some modern e-collar trainers are using these devices primarily for “negative reinforcement” (removing something unpleasant reinforces the behavior). I also thought about some of the shelter dogs I’d worked with: in certain situations, waving a side of beef in their face would not get their attention. (How little I knew then!)

Now, however, I’ve learned more and I’ve seen more, and, though I still understand the popular appeal of e-collars, I have significant concerns — related to the welfare of dogs and the human-dog bond — that, for me, far outweigh the neatness factor. To keep this page from becoming a book manuscript, here’s a good article that acknowledges the modern approach to e-collars (better than the old ways!) but describes the downsides in a way I find refreshingly fair and informative. Yes, the author is arguing against e-collars, but she does so with full awareness of how their use has evolved in recent years.

Perhaps most convincingly, research suggests that even the modern negative reinforcement approach to e-collar training is no more effective than positive reinforcement conducted over the same duration and for dogs randomly assigned to training approaches for recall problems.

Want more science on dog training methods? Here y’go!

Despite a range of methods, all of my trainer friends and colleagues have had something to teach me, and I respect their skill and compassion, even if we disagree on approaches and equipment. My experiences and education have led me to believe that we trainers should prioritize methods that create or strengthen the human-dog bond, not methods that can degrade that bond or result in unintended negative associations that can affect behavior and welfare. We should focus on positive reinforcement (which is not just about giving dogs cookies!), while avoiding or minimizing the use of aversive stimuli in training.

This is where I am today, but it’s not where I started, so I recognize that many compassionate dog trainers and guardians have followed a different path and are in a different place in their opinions about various methods.

I don’t like using labels — in dog training or anywhere else. First, because they can be polarizing. Second, because they tend not to be 100% accurate.

Like “force-free” — realistically, one cannot entirely eliminate force in training (hello, hard-pullin’ pups!), though absolutely we should minimize it. Or “positive-only” — because though a trainer like myself might focus on positive reinforcement, we might also use techniques the eggheads would call “negative punishment” (e.g., a timeout) or certain forms of “negative reinforcement” (any CAT fans out there?). We do generally avoid negative reinforcement though, because it’s hard to keep aversive stimuli from causing pain, fear, anxiety, or just a layer of stress. If that stress is added onto other stressors in the dog’s life, it can push a dog too far psychologically. The methods we avoid like the plague are, in nerdspeak, those falling into the “positive punishment” category. There is nothing positive about positive punishment! It’s the application of something unpleasant enough to reduce the likelihood/frequency of a behavior occurring in the future.

I do use the word “humane” as a way to help visitors to our website get a quick sense of our methods, but I recognize that this term is highly subjective. I am certain that every trainer I know feels that they are humane and would argue that point strongly.

If I have to choose a label, I’ll go with LIMA: least intrusive, minimally aversive, with the definition provided by the International Association of Animal Behavior Consultants.

If that sounds like the approach you’re looking for — regardless of what methods you’re using now or have used in the past — get in touch!

Muttamorphosis

Dog Training

301-693-9661